Jellyfish

This is a tricky subject, so we should put it in context first. We have been out snorkelling thousands of times, and have been stung by jellyfish on no more than a handful of occasions. It's not something that happens often. So, when we go snorkelling, are we usually worried about jellyfish? No. We're not.

On the other hand, being stung by a jellyfish can be very painful, and on rare occasions is fatal. So, caution is a good idea.

There are more than 2,000 species of jellyfish, and about 5% of them sting. We have swum through shoals of jellies following a guide, brushing them aside. On the other hand, 5% means about 100 species. It's best to keep away from jellies when you see them, and if we start to get stung, we always get out of the water.

Above: You can do this, if you have a guide and you know what you're doing.

Below: Portuguese man o'war. Don't go near these, even when they're stranded on the beach.

What are they, and how do they live?

Jellyfish are not fish. They are invertebrates that travel round the world by self propulsion, wind, and tides. Usually they live by eating plankton, which they catch by trailing stingers which immobilise their prey. These stingers are problematic for humans, in that they can sting us too.

The classification of what is a jellyfish is also tricky. The well-known Portuguese Man o' War, for example, is not a jellyfish, but a colony of polyps all acting together (it's in a group called Hydrozoa, like fire coral - which explains why you can get a nasty rash if you brush up against certain coral types).

Working on the basis that you don't really care what something is, if it's going to sting you, we'll use a relaxed version of what is classified a jelly and what isn't.

Where do we find them?

They can crop up anywhere, depending on the weather and the tides. But they generally vary in terms of how much damage they do to humans.

In the U.K., the BBC recently quoted the Marine Conservation Society in saying that jellies around Britain are not very dangerous - they can give you a nasty sting, particularly the Lion's Mane, the Portuguese Man o' War, and the Mauve Stinger. http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-36922987, but it's unlikely they will kill you.

There were reports of a large shoal of Portuguese Men o' War approaching the U.K. in 2017, and they pack a nasty sting. They trail their tentacles tens of metres behind them, so you won't always see them. A friend was stung while swimming off Cornwall, and it wasn't pleasant. These organisms look particularly attractive when they wash ashore, they look like a string of balloons - but don't touch them, they can still sting.

The Marine Conservation Society has published a helpful identification leaflet for British stingers - https://www.mcsuk.org/downloads/wildlife/Jellyfishguide.pdf

They make the general point that, even if a jellyfish is classified as harmless, it's a bad idea to touch it.

Above: jellyfish sting off Cornwall, UK, Jan 2016. Photo: Jim Rose. It's his leg, too. He said it really hurt...

Below: the Mauve Stinger. Common in Europe.

Mediterranean

In the Spanish Mediterranean, thousands of people swim in the sea, and on occasion there are a lot of jellyfish. Hundreds of swimmers are stung every day, with one estimate of 15,000 stings a year (the Booker-prize-listed novel Hot Milk features a Spanish lifeguard whose main job is dealing with jellyfish stings).

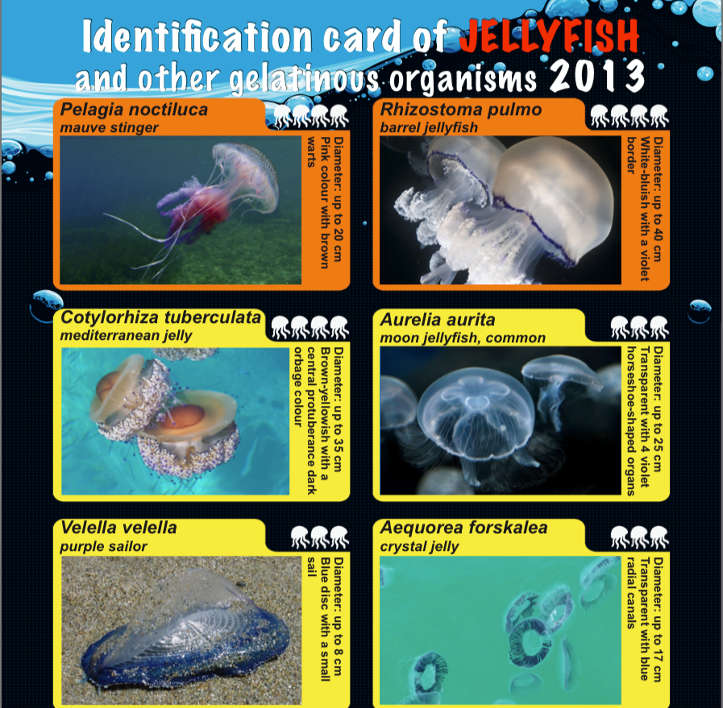

Pelagic Noctiluca, or the Mauve Stinger, is common, but there are others. The EU funded a booklet in 2013 identifying the different types of jellyfish and how to treat the stings. Identification Guide and Stinging Treatment for Jellyfish and other Gelatinous Organisms can be found at http://jellyrisk.eu (go to the Downloads section). Again, these stings can be painful but are not usually fatal.

Australia, Far East

In Australia, it's a very different situation. They have box jellyfish there in certain months - both the larger variety, known as the sea wasp, and the smaller variety, the Irukandji. I don't want to get this wrong, so I'm going to quote www.bugbog.com:

The Box Jelly (aka Sea Wasp or Chironex Fleckeri) are the most toxic creatures on Earth. They and 20 close relatives are found off the shores of Northern Australia, PNG, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. This marine animal has a boxy bell head the size of a basket ball, 4 parallel brains (one on each corner), 24 eyes and 60 anuses! (says Dan Nilsson, a vision expert from the University of Lund in Sweden). Then there are 5,000 deadly stinging cells on each of its 10- 60, two metre long tentacles.

These are the nasty killers of the sea, trailing venom tentacles up to 2 metres behind them. This box jelly kills one person a year in Australia, though this may be an underestimate - the pain is so extreme that it can cause heart attack or drowning. This is one jellyfish to avoid. Problem beaches are usually signposted, and the danger months are October to May.

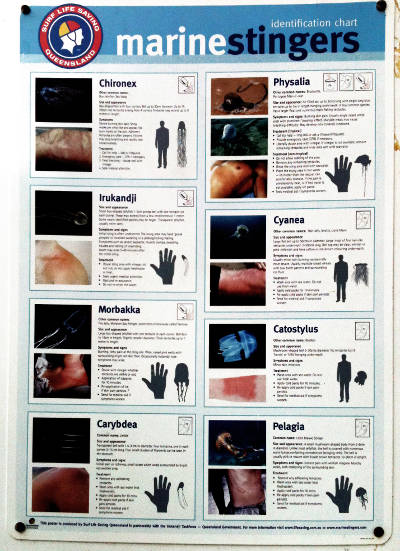

The Box Jelly and the Irukandji cause a lot of inconvenience. Irukandji are the size of your fingernail, and lurk offshore off Northern Australia. Certain currents can bring them to shore, which means along the Queensland coast, at certain times of year, you can't even paddle in the water, and you can swim in the sea only in specially-screened off stinger areas. A sting from the Irukandji isn't as painful as the Box, but it can cause Irukandji fever which can occasionally kill.

The authorities in Australia take this problem very seriously, but tourism imperatives mean that you can still end up in parts of Queensland between October and May and find that you can't go snorkelling, unless you wear a Lycra suit. So check before you go.

Chart produced by Surf Life Saving Queensland in partnership with the Irukandji Taskforce. For more information visit www.lifesaving.com.au or www.marinestingers.com.

What do you do if you're stung by a jellyfish?

First, try to avoid being stung. Ask in the hotel or ask a lifeguard about jellyfish before you get in the sea: if you see jellyfish, avoid them: never touch a jellyfish, even a dead one: and if you're in the sea and get stung, get out immediately.

There are some jellyfish repellents on the market, but we're not sure if they work. We have tried them out and we weren't stung, but then we don't get stung 99.5% of the time. Is that proof that they work, or just coincidence?

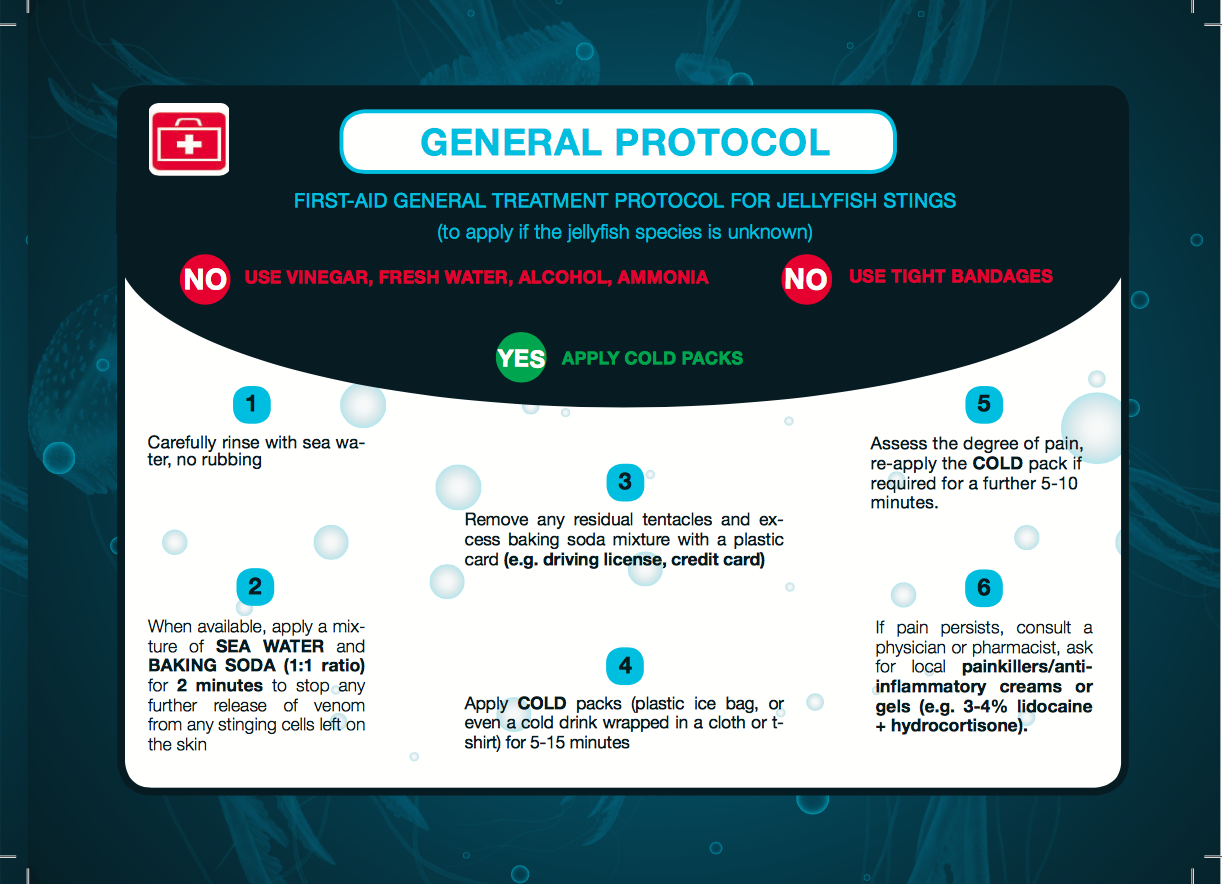

If you do get stung, you should understand the mechanisms involved. The science is complex, but essentially the sting mechanism lays a series of micro-stings on your skin - called nematocysts or cnidocists. Think of these micro-stings as harpoons, ready to inject venom into your body. Some harpoons have already triggered, which is why it hurts, but there are others on your skin, which can also be triggered if you take the wrong action. You have an already-hurting unexploded bomb sitting on your skin.

So: don't rub it - you'll trigger more harpoons.

Don't pour fresh water or alcohol on - it will make it worse.

Don't pee on it - that actually doesn't help (except for box jellyfish).

What do you do? That depends on what kind of jellyfish you've been stung by. As a general rule, wash the area in seawater (but don't rub it!). See if you can see any stings, and remove them with a clean object such as a credit card or tweezers (and wear medical gloves). Vinegar can be helpful with box jellyfish but not that many others - and it can make it worse by triggering more venom.

So - wash in sea water

See if you can extract the stings.

Get medical attention.

Here's a page from the Jellyrisk document: basically, they are saying that jellyfish stings aren't that well researched, and that there isn't a one-size-fits-all remedy for a jellyfish sting. But it's worth visiting the website: http://jellyrisk.eu.

Further information

Marine Conservation Society Jellyfish guide

https://www.mcsuk.org/downloads/wildlife/Jellyfishguide.pdf

PERSEUS (Policy-Oriented Marine Environmental Research in the Southern European Seas) jellyfish guide

http://www.perseus-net.eu/en/species_of_jellyfish/index.html

jellyrisk.eu

http://jellyrisk.eu/media/cms_page_media/115/27.Jellyfish%20Guide%202014%20-%20Spain%20(english).pdf

British Marine Life Study Society Jellyfish page

http://www.glaucus.org.uk/Moonjell.htm

Marine biologists are working on a more academic approach, called http://jellywatch.org, which aims to track jellyfish movements around the world. It is described as a jellyfish version of Google Maps

There are currently two apps available - the Jellyfish App https://thejellyfishapp.com, in English, French, Chinese and Spanish, and started out in Australia: and there's an app in Spanish called infomedusa, which tracks jellyfish movements round the coast of Spain.

http://www.infomedusa.es

Usual warning: we have made every effort to make sure this information is correct and up-to-date, but you need to check it all yourself.

© Garreg Lwyd Ltd 2017